Dario Argento followed up his eerie, beautiful masterpiece Suspiria with something of a sequel, Inferno, which expands on the previous film's mythology about witches and evil forces, focusing on another member of a trio of sinister "mothers" who are spread out across the world. Like its predecessor, though, Inferno is more concerned with atmosphere and a general mood of dread and terror than it is with narrative sense; this film is even less coherent than Suspiria, its plot laughably fragmented and bizarre, placing the emphasis entirely on Argento's typically chilling set pieces, his gorgeous lighting schemes and cinematography.

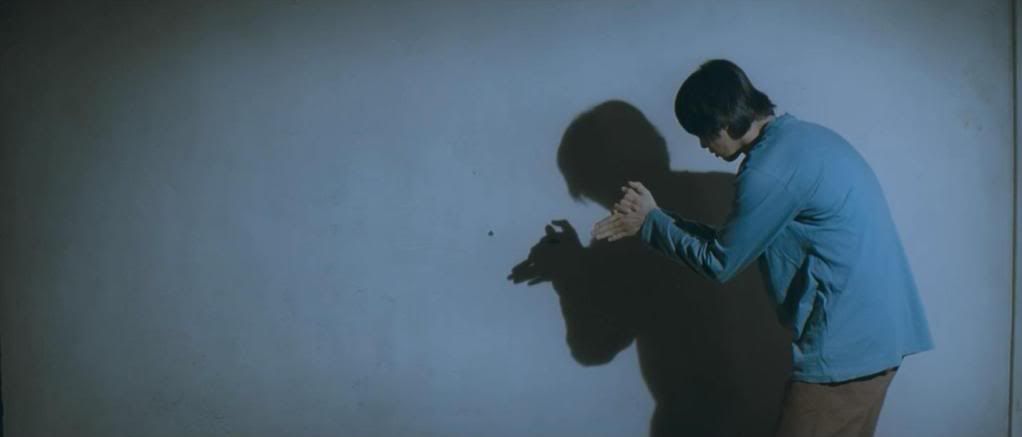

Inferno never even quite settles on a central protagonist: instead, a number of people begin investigating strange occurrences in both Rome and New York, including Rose (Irene Miracle), her brother Mark (Leigh McCloskey), and Mark's classmate Sara (Eleonora Giorgi). Argento jumps back and forth between multiple potential protagonists, but few of them stick around for long, except for Mark, who's a curiously passive character, plagued by fits and ailments that prevent him from doing much more than stumble aimlessly and ineffectually through the film, following a strange and unsettling trail of clues to the film's fiery climax.

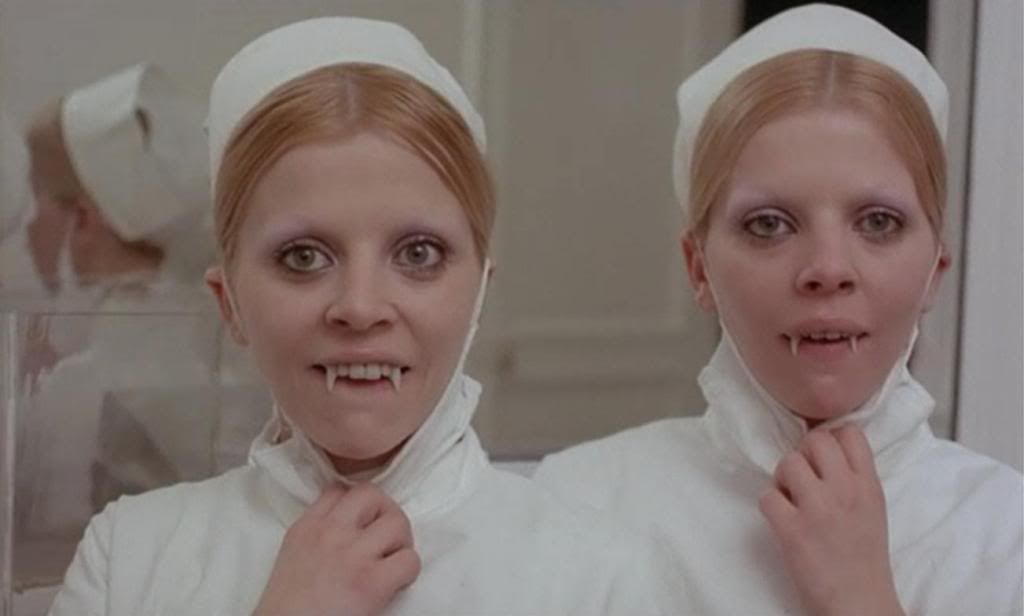

The emphasis here is not on the plot or the disposable characters, but on the beautifully disturbing imagery that Argento (in collaboration with his mentor Mario Bava, who crafted many of the film's optical effects and set designs) applies to the film's series of creepy murders. There's an almost surreal sensibility to the film at times. At one point, as a prelude to a murder, Argento cuts in a never-explained series of shots — a lizard eating a moth, gloved hands cutting the heads off paper cutouts, and a woman being hanged — that suggest the violence to come but are otherwise all but non-sequiturs.

This nonsensical strangeness reaches its apex with a grisly, torturously prolonged sequence late in the film, when a man is attacked by rats at a pond in Central Park, the rats swarming over him and gnawing at him as he splashes about in the water. Argento allows this grisly death scene to stretch out for a long time, until a nearby hot dog vendor suddenly hears the man's screams and goes running towards (and then, magically, across) the pond, seemingly to save the floundering victim — until he pulls out a massive butcher knife and begins hacking at the man's neck instead. It's darkly comic and utterly unexplained, beyond the fact that the malevolent "mothers" can apparently possess and control anything and anyone, from rats to people to the cats that tear apart another of the film's victims.

This was a troubled production for Argento, who fell ill during filming and was not even on-set for some scenes, turning parts of the film over to assistants (apparently including Bava). And yet the film is unmistakeably steeped in the same aesthetic that drove Suspiria, associating death and terror with the distinctive red and blue colored lights that bathe so many of Argento's sets, even when it makes no conceivable sense — when Mark pries up the floorboards of his sister's apartment, he climbs down into a crawlspace that is, unaccountably, lit with that same eerie, striking primary color palette. The film's opening scenes, in which Rose prowls through the dilapidated basement beneath her towering, gothic apartment building, memorably evoke the same slowly accumulating tension as Suspiria, with the wide-eyed heroine stalking through pools of shadow and colored light.

The sequence climaxes with a stunning underwater scene (apparently not even directed by the ailing Argento) in which Rose descends into what looks like a little puddle of water but opens up into an entire underwater room. Like a lot of things about this movie, it doesn't make a whole lot of sense, except as a dreamlike passage from ordinary life into the unsettling other world that lies beyond our own. Something as prosaic as dropping one's keys leads to an eerie encounter with death, and the heroine can step into a puddle and emerge into a submerged chamber, a remnant of another time, offering grim portents of the fate awaiting her if she continues her investigation. The sequence has the slow, dreamy quality of an underwater ballet, the fear and tension of the sequence eroticized by the way the woman's clothes cling wetly to her body, her skirt billowing up around her, her lithe form diving and slashing through the water as the suspense builds and builds. There's an almost fetishistic quality to the scene, which is also embodied in the way that Argento abstractly associates injuries to the hand with impending doom — for no apparent reason, throughout the film, seemingly innocuous hand injuries almost always precede death and terror.

Inferno is a worthy follow-up to Suspiria. It is even more reliant on atmospheric imagery than its predecessor. It's a pure mood piece that's all about its lurid lighting, crisp sound design (including a score, by progressive rock legend Keith Emerson, that builds to operatic prog-metal bombast at the film's climax) and grotesque set pieces. Argento, in these films, is abstracting horror until the silly, hole-ridden plot is irrelevant, and all that matters is the eerie beauty with which the film presents its suspense and its bursts of violence.