The Grapes of Death marked a return to form for the idiosyncratic horror auteur Jean Rollin. After 1974's remarkable but commercially unsuccessful Lips of Blood, Rollin, unable to get even the typically miniscule budgets his particular brand of surreal, dreamlike horror required, began churning out straight-up softcore porn under the aliases Michael Gentil and Robert Xavier. The Grapes of Death, produced in 1978, four years after his last horror project, was Rollin's retreat from the adult film ghetto. It's a fantastic return, too, with Rollin tackling the zombie genre and adapting his sensual, hypnotic aesthetic to this creepy tale of a rural wine-producing region overrun by shambling, rotting, diseased and insane farmers.

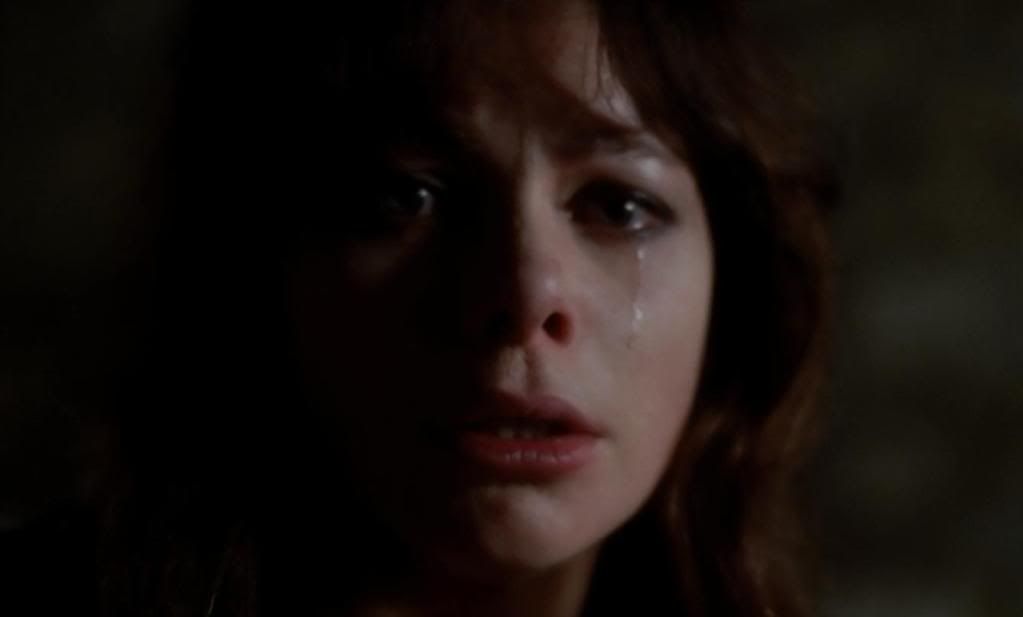

This decay of civilization is seen through the eyes of Élisabeth (Marie-Georges Pascal), a young woman who's planning to visit her fiancé at the winery he manages. Instead, her train journey is interrupted by a zombified man who kills her friend and chases her off the train into a typically desolate Rollinesque countryside. This rural landscape is alternately brightly sunny and shrouded in fog, utterly without logic or concern for continuity. The film has a strangely gorgeous, pastoral atmosphere that clashes against the periodic outbursts of sloppy gore and disgusting, smeary makeup effects. Fleeing from her zombie pursuer, Élisabeth runs across a foggy bridge, surrounded in fluffy white clouds, then runs into a large open meadow that Rollin films in a stunning wide shot, the sun a glowing blue pinprick just barely cutting through the thick soup of the fog. Élisabeth arrives at a cemetery, looming out of the fog with massive stone crosses atop its locked gate, but soon after, the fog disappears in between shots, and the heroine is running across a rocky, barren hillside, bathed in gorgeous summery sun.

Weather and landscape are both prone to this kind of slippage in Rollin's films, with their uneven regard for the niceties of continuity. The countryside itself provides many of the chills here, with this terrified young woman stumbling across this desolate, unwelcoming land, coming across crumbling stone buildings in various states of decay and destruction, as though the land was already abandoned and falling apart long before this zombie plague further decimated the region. Rollin has always loved the gothic ruin of collapsing castles and old buildings situated in bleakly beautiful, unpopulated surroundings. He makes these scenes both sinister and oddly appealing, because he's obvious fascinated by the poetic ruin of these landscapes even as he uses them as foreboding settings for tales of death and terror.

Rollin is adept at finding a languid, melancholy form of poetry in the trashy, violent, sexually charged B-movie material that drives the often fragmented narratives of his films. Here, he makes his zombies more sad than terrifying, as they stumble around, their faces melting with oozing open sores that pour multicolored liquids down their cheeks and over their foreheads. The effects are primitive and ugly, and also somewhat disgusting — especially in the disturbing scene where one zombie repeatedly smashes his head against a car's window, leaving pus-yellow streaks on the glass until he finally manages to shatter it. Rollin makes this zombie plague explicitly a kind of disease, caused by pesticides used on wine grapes, and the sufferers of the plague are in various states of mental and physical decay, some of them utterly blank, their minds erased, and others tragically seeming to understand that they're losing their minds and being possessed by violent urges.

There's a strange poignancy to these zombies. When the initial zombie is first chasing Élisabeth, he abruptly gets tired and slumps down to a seat on the railroad tracks, cradling his head in his hands, exhausted and frustrated; Rollin, interestingly, pauses to consider the emotions of the zombie, too tired to continue chasing his prey. Later, Rollin gives one of the zombies a surprisingly affecting (and creepy) death scene, using the last of his energy to bloodily kiss the severed head of the woman he'd loved and killed, whose head he'd been carrying around in front of him like a talisman ever since.

Élisabeth's journey across the countryside is structured around her encounters with various people affected in various ways by the plague. She leads the blind woman Lucie (Mirella Rancelot) through the wasteland of a ruined, burning village with dead bodies strewn everywhere, the blind woman unable to see the wreckage all around her — and later, unable to see the zombies, her former neighbors, gathering around her and slowly closing in. Towards the end of the film, Élisabeth falls in with a pair of farmers, unaffected by the disease because they drink beer instead of wine, who provide an opportunity for a sudden diversion into political commentary. The action suddenly halts for these two to briefly discuss politics, improbably connecting the zombie outbreak to the French Resistance and modern anti-militarism. It's such a clumsy and truncated bit of forced commentary that it almost feels like a parody of the kind of social issue messages that, following George Romero, have become de rigeur for zombie movies.

The film's most memorable cameo appearance comes from Brigitte Lahaie, an adult film actress who had appeared in one of Rollin's earlier porn ventures, and had apparently impressed the director: she'd go on to be an important muse in his next few features, and is here already a formidable screen presence. Her unnamed character (appropriately credited only as "la grande femme blonde") is a mysterious woman who Élisabeth encounters while fleeing from the zombies. Seemingly unaffected by the plague — in a typical Rollin flourish, she eagerly shows off her naked body to reveal the lack of rotting wounds — she nevertheless projects a curious, magnetic menace in her ferocious, teeth-baring smile. Her teeth permanently clenched, she looks like she's either holding back some intense inner turmoil or preparing to devour anyone in her path. She makes only a brief appearance here, but her unhinged, terrifying performance is unforgettable, especially since she also strikes some unexpected notes of poignancy within this portrayal of a deranged psychopath.

Moody, chilling, poetic and strangely moving, The Grapes of Wrath is another fantastic, utterly original horror piece from Rollin. It's slightly more straightforward and conventionally horrific than many of his earlier films, with more gore and action, but it's still primarily reliant on its dreamlike atmosphere, on the sense of an eerie journey across a haunted wasteland where the terror arises as much from the abstract aesthetics as from the actual supernatural or monstrous threat.

4 comments:

This is one I hope Kino/Lorber will be picking up. Want to see the film, but I want K/L to release it like they have all those others.

Great article and the pictures especially with the head was so awesome!

Recently watched and reviewed this one, loved it, in an interview thats included in the dvd Rollin says that his movies are void of religious or supernatural themes, "I dont need religion in my movies" he says, this is probably why even his vampires aren't afraid of crosses or any other supernatural mumbo jumbo. His monsters were more grounded on reality, which probably explains these zombies surfacing because of a toxic thats sprayed on the crops.

Good review, Rollin is awesome.

"Weather and landscape are both prone to this kind of slippage in Rollin's films, with their uneven regard for the niceties of continuity. The countryside itself provides many of the chills here, with this terrified young woman stumbling across this desolate, unwelcoming land, coming across crumbling stone buildings in various states of decay and destruction, as though the land was already abandoned and falling apart long before this zombie plague further decimated the region."

I have seen a few films by Rollins, this one included. As always Ed, you have a brilliant grasp of this director's artistry, which in one sense is a firm disclaimer against a vociferous minority who take aim at Rollin's audacious excess. I think of Franco and Fulci is this equation, though Rollins leave both of those well in the rear. The segment I include above is to honor your descriptive writing powers, and in establishing a vital point in appreciating Rollins. Your continued discussion on the 'melancholy form of poetry' couched in the B movie material is really peeling away the gauze persuasively, and to find the poignancy in these zombies recalls Romero's earliest work in that sense.

Extraordinary piece that fully deserves the widest exposure!

Post a Comment