Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's version of Jacques Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann is a brightly colored, theatrically decorative celebration of lavish imagery and ecstatic dancing. This was the next logical step for Powell and Pressburger after The Red Shoes, their classic tragic romance about a ballerina torn between her love of the dance and her love of a man. The gorgeous, elaborate dance sequences in that film are here extended into a full staging of an opera/ballet, with everything sung, and all the drama embodied in graceful dances. As in that earlier dance film, despite the theatrical aesthetic of the sets, this is a dazzlingly cinematic adaptation, taking place in a sumptuous world of unreality, its time-spanning love stories leaping without warning down to the scale of dancing puppets or blurring the boundaries of reality with supernatural interventions.

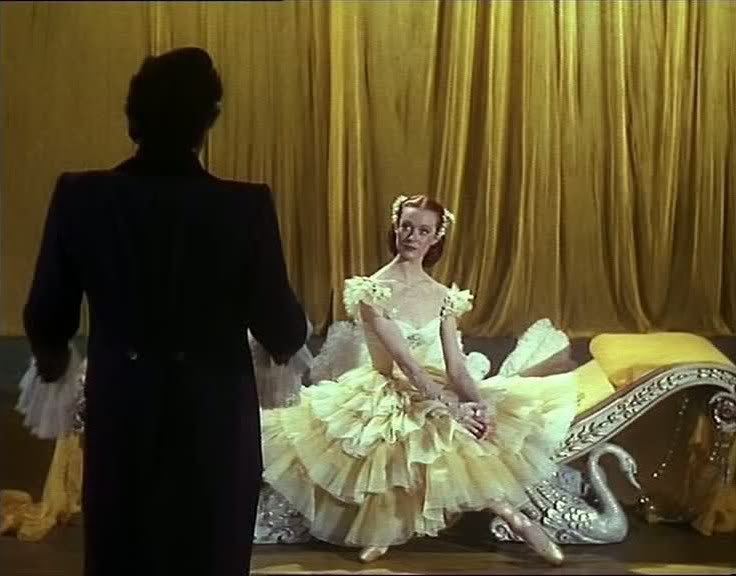

It's the story of the poet Hoffmann (Robert Rounseville), who in the framing story begins relating a trio of tales from his past, each of them concerning a woman he loved and lost. Each of these segments is a self-contained story in itself, providing further opportunity for Powell and Pressburger to vary the aesthetics and tone of the film. Throughout each of these stories, continuity is provided by the recurrence of actors playing multiple roles, particularly Robert Helpmann, who in each of the film's segments, including the framing story, plays Hoffmann's diabolical nemesis. In the first segment, the young Hoffmann falls in love with Olympia (Moira Shearer), a doll constructed by Spalanzani (Léonide Massine) and the mad inventor Coppelius (Helpmann). They present her as Spalanzani's daughter, and Hoffmann, still an innocent youth, untutored in worldly things, falls completely for the ruse, bowled over by the beauty and elegance of the doll — a rather elegant metaphor for youth's tendency to seek perfection in love, to elevate the loved one to the pristine, passive perfection of a porcelain doll. This section's aesthetic is sugary and bright, a fluffy confection with frilly yellow drapes circling the room where Hoffmann falls for the fake girl while watched over by an audience of other puppets.

The songs are often spiked with an edge of naughty wit, as when Hoffmann's friend Nicklaus (Pamela Brown) comments that Olympia is preparing "to show off her technical pieces," a double entendre that earns a collective shocked glance from the assembled puppet audience, and prompts Nicklaus to smile at the camera, as though acknowledging the naughty pun about the mechanical girl. A perverse undercurrent runs through this whole sequence as the besotted Hoffman obliviously pursues the doll, delighting in her clockwork dancing and gestures of love, all of it playing out with the kind of kinky strangeness that motivated Ernst Lubitsch's rather similar silent comedy Die Puppe. The perversity of this set-up reaches its climax in the surprisingly chilling final scenes, where Coppelius and Spalanzani fight over Olympia and wind up tearing her to pieces limb by limb, knocking her head off, tearing off her arms and legs, leaving behind just a single leg dancing gracefully in the void, and her head on the floor, blinking with mechanical clicks, as the final image of this sequence.

In the film's second segment, Hoffmann is seduced by the alluring Giulietta (Ludmilla Tchérina), who steals the unsuspecting man's soul by getting him to glance into an enchanted mirror. In contrast to the bright primary colors of the previous segment, this story is draped in lush shadowy textures, its colors dark greens and purples. There are mirrors everywhere here, reflecting the dishonesty and trickery of this false love, culminating with Giulietta's sensuous, snake-like dance of triumph, in a mirror where she is reflected but Hoffmann, his reflection stolen along with his soul, does not appear. It's a masterful sequence, the woman's moves making it seem as though she's weaving her body around the man, dancing triumphantly around him, even though he does not appear in the shot, his absence structuring her dance anyway.

Later, Hoffmann descends a gloomily lit staircase and takes a ferry ride into the underworld, pursuing his missing reflection. This whole segment is steeped in gothic imagery, culminating in a duel in the underworld, overlaid with an image of Giulietta's beautiful but deadly face superimposed over the river of the dead with its black-robed ferryman. Tchérina's performance as Giulietta exudes a raw sexuality that infuses the entire segment, giving it the stormy, passionate, dangerous quality of a doomed romance.

In Hoffmann's final story, he loves the sickly opera singer Antonia (Ann Ayars), who's subjected to the dubious medical care of the sinister Dr. Miracle (Helpmann). In a dazzlingly surrealistic sequence, Miracle, looking like the vampire of F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu, stalks after the girl through a surreal, distorted dreamscape, as she fruitlessly flees the menacing figure with his pale white face, black-rimmed features, and black robes. She runs through a maze-like set, running into one door and suddenly appearing out of another, always returning to the room in which Miracle looms threateningly over her bed, with Antonia unable to escape.

This sequence reaches a fever pitch with an even more spectacular sequence in which Miracle tries to seduce Antonia into breaking her vow to Hoffmann: she's been forced to choose between her love of music and her love of Hoffmann, and Miracle offers her a career as a famous opera singer to make her forget her lover. As Miracle tries to win the girl's soul, he enlists the spirit of her mother, a famous singer herself, and the music becomes ecstatic and frenzied, with multiple overlapping voices, as the setting shifts into a hazy, unstable dreamworld with Antonia dancing amidst the chaos, finally being almost swallowed by flames as the music reaches its wild, intense peak.

As Antonia's tragic tale reaches its conclusion, it fades seamlessly back into the framing story through a series of images in which Helpmann appears in his various guises as the film's multi-named villain, embracing each of the film's women in turn, before a brief coda in which he enacts his final revenge on his enemy Hoffmann, by stealing away the last of the film's women, the dancer Stella (played again by Shearer). Throughout all these parallel romances, the emphasis remains squarely on the colorful, at times downright avant-garde visuals that Powell and Pressburger apply to this material. The film's aesthetic vibrancy allows even those who might not connect to the operatic music — like me, admittedly — to get swept up in the emotional intensity and garish beauty of the film anyway.

3 comments:

"Later, Hoffmann descends a gloomily lit staircase and takes a ferry ride into the underworld, pursuing his missing reflection. This whole segment is steeped in gothic imagery, culminating in a duel in the underworld, overlaid with an image of Giulietta's beautiful but deadly face superimposed over the river of the dead with its black-robed ferryman. Tchérina's performance as Giulietta exudes a raw sexuality that infuses the entire segment, giving it the stormy, passionate, dangerous quality of a doomed romance."

Masterful segment here Ed! Yes it is easy to get swept up in this stylish fantasy, based on the most rightly celebrated opera by Offenbach, one that weaves it's phantasmogoric spell even more compellingly than any staging of the opera. (I have seen three different productions over the years). The 'Baccarole" of course in the highlight of the opera and of this film, and it's cinematic exhilaration of the highest order. I adore this film, and mich appreciate this superlative scholarly treatment! It is unquestionably one of the greatest "opera films" ever made.

Hooray! I bloody love this movie. It's an absolute jewel.

Unquestionably one the weirdest films ever made. Having scaled the heights with The Red Shoes its no surprise P&P went full bore insane with this work -- which is one of the three films Josef Von Sternberg cites as his favorites (the other two being Last Year at Marienbad and Marco Ferreri's The Wheelchair)

An ideal double feature wiht Fellini Casanova

Post a Comment